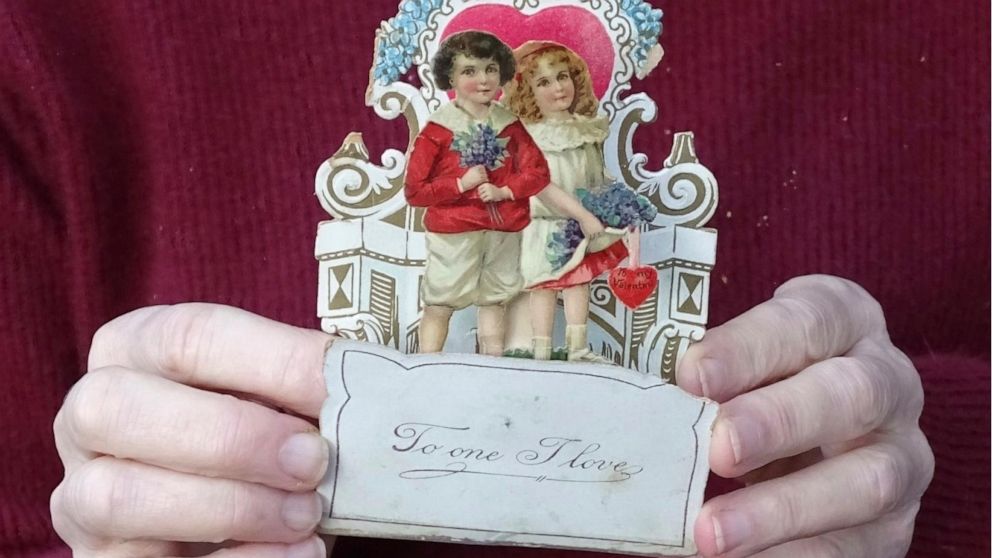

NEW YORK — It was Valentine’s Day 1917 in the Minnesota farming village of Lewiston, and Fred Roth — a fourth grader — seems to have come up with just the way to express his love for his sweetheart, Louise Wirt. He gave her a card.

The folding, pop-up Valentine’s Day card, on stock so heavy it remains in good shape 106 years later, reads: “Forget me not!/I ask of thee/Reserve one spot/In your heart for me.”

And so she did. Years later they married, and Louise displayed the cherished card, tucked into the fretwork of a bedroom dresser, for decades to come. She pointed it out to her daughter, and later to a granddaughter, me, and it remained near her bedside until her death at 91, a token of lasting love.

Although the message was in English, the card is printed with the word “Germany” and is seemingly imported, as were many cards of that era. Small companies in the U.S. also were part of a flourishing commercial card business.

Hallmark, which arrived on the scene in 1916, estimates that today, 145 million Valentine’s Day cards are exchanged annually, not including the kids’ valentines popular for classroom exchanges.

Fertility-related customs and rituals have been celebrated in mid-February since pagan times, says Emelie Gevalt, curator of folk art and curatorial chair for collections at the American Folk Art Museum in New York City.

Tokens of affection varied: In the 1600s, the practice was to give pairs of gloves in mid-February, she says.

“By the 18th century, we start to see something that really begins to resemble modern Valentine’s cards,” she says. “In the 19th century, this evolved further to the point where popular ladies’ magazines like Harper’s Weekly published instructions for readers on how to craft them.”

There have long been both earnest, heartfelt Valentines like Grandpa Fred’s, and ones in a more teasing, playful vein.

The museum’s collection includes a number of lovingly crafted tokens of affection from various periods. “You see the heart motif quite a lot,” Gevalt says.

Although not specifically linked to Valentine’s Day, an exhibit at the museum opening March 17, “Material Witness: Folk and Self-Taught Artists at Work,” features two examples of “fraktur,” exuberantly decorated watercolors made by German immigrants in Pennsylvania. One is called “Inverted Heart,” and another depicts a labyrinth.

“They were really dazzling objects, including motifs of flowers or hearts. The playfulness and…

Click Here to Read the Full Original Article at ABC News: Health…