The 3,500-year-old pockmarked skeleton of an ancient Nubian woman could be one of the earliest known cases of rheumatoid arthritis in the world, scientists say.

Archaeologists discovered the woman’s skeletal remains in 2018 while conducting excavations at a cemetery located along the bank of the Nile near Aswan, in southern Egypt. Analyses revealed that she would have stood around 5 feet (1.5 meters) tall, been around 25 to 30 years old when she died and lived sometime between 1750 and 1550 B.C. The researchers published their case study in the March issue of the International Journal of Paleopathology.

Because the skeleton was so well preserved and contained most of its bones, including its hands and feet, the researchers were able to conduct a thorough osteological analysis of the remains.

“In many archaeological cases, you don’t often get the full skeleton,” lead study author Madeleine Mant, an assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Toronto in Canada, told Live Science. The woman’s well-preserved remains “gave us the chance to look at this disorder that actively attacks the small bones of the hands and feet and talk about it with a little bit more security,” she said.

Analyses of the woman’s extremities revealed that she likely had rheumatoid arthritis (RA), an autoimmune disorder in which the immune system mistakenly attacks the body’s tissues, resulting in inflammation, particularly in the joints. Today, doctors diagnose the condition using a combination of bone imaging and blood tests that look for proteins tied to inflammation and for antibodies trained to attack the body’s tissues.

Related: Ancient Egyptian teenager died while giving birth to twins, mummy reveals

Of course, in this case, the scientists could only look at the bones.

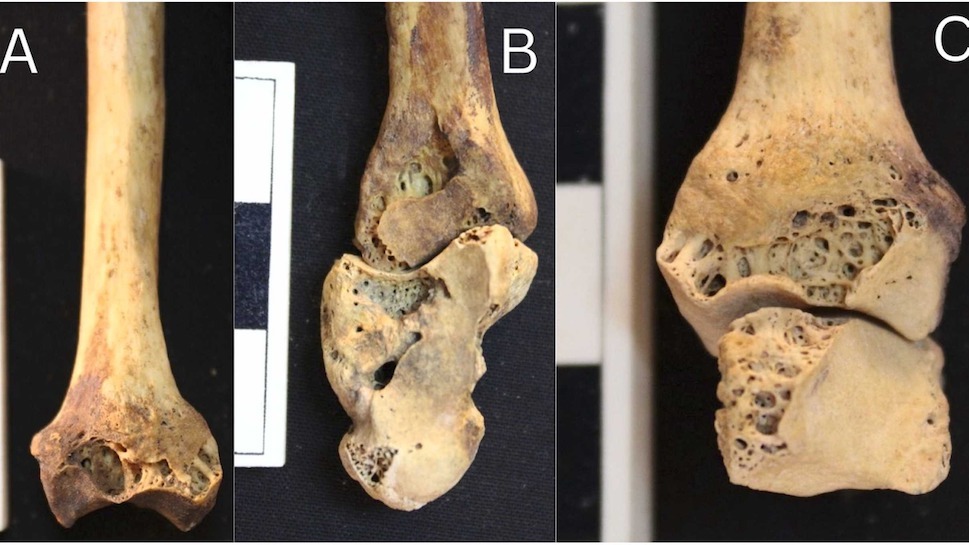

“The joint surfaces themselves weren’t damaged, and in a lot of other types of arthritis you get destruction where the two bones meet,” study co-author Mindy Pitre, an associate professor and chair of anthropology at St. Lawrence University in New York, told Live Science. “In our case we had no destruction of where the bones meet.”

Instead, researchers spotted “cavitations or erosive lesions with smoothed-out holes” in the woman’s bones, which point to a rheumatoid arthritis diagnosis, Pitre said.

“I’m used to seeing osteoarthritis — it’s one of the most common joint conditions that we see archaeologically,” Pitre added. “It looks like bone on bone where you get this smooth look that…

Click Here to Read the Full Original Article at Livescience…