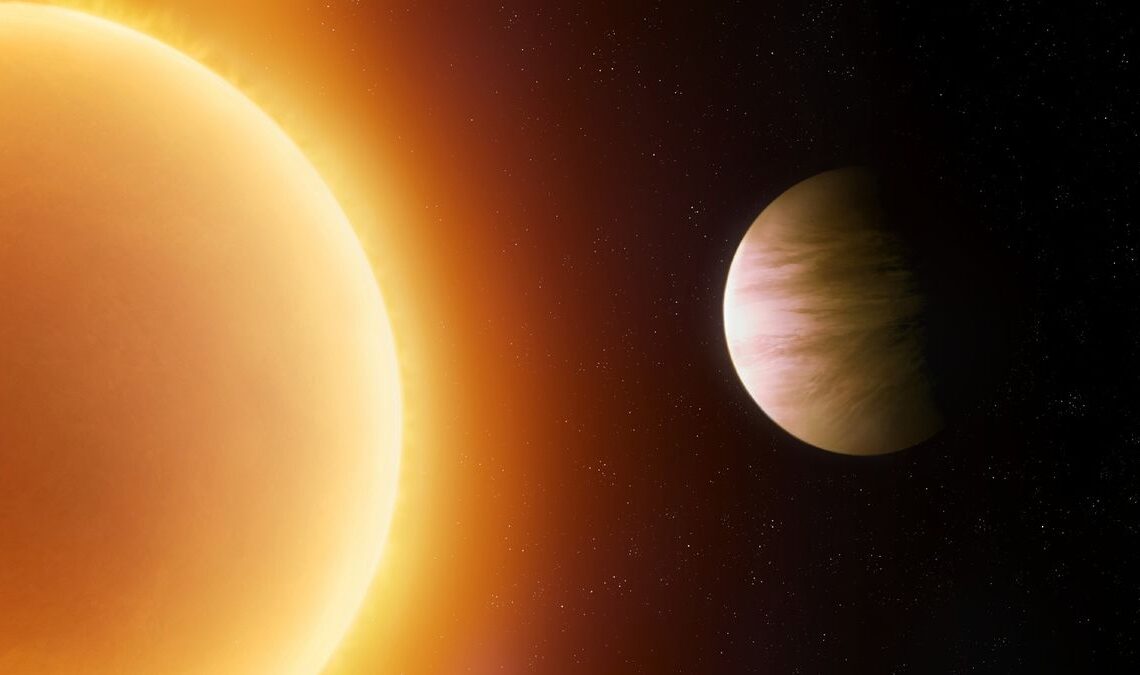

The famed science fiction author Isaac Asimov called them “ribbon worlds” — planets forced to always show one face to their parent star. The star side is locked in perpetual day, its sun never dipping below the horizon; indeed, its sun never even moving at all, fixed in place as if time itself stood still. The far side is trapped in perpetual night, a sky blazing with the light of thousands of stars, never knowing the warmth of its parent star.

And in between those two extremes, there’s a special place: a terminator line, the boundary between night and day, a region of infinite twilight. Caught between the two extremes, this ribbon that stretches like a girdle around a planet might — might — just be a home for life, neither too hot in the never-ceasing glare of the star nor too cold in the infinite night.

Astronomers are especially interested in the habitability of these kinds of planets because they are incredibly common in the universe. The physics behind them is called tidal locking — the same reason the moon always shows the same face to Earth. Stars can do the same thing to their planets. Indeed, in our own solar system, Mercury is almost tidally locked with the sun, but the gravity of Jupiter keeps the smaller planet rotating, albeit very slowly.

Related: Aliens could be hiding in ‘terminator zones’ on planets with eternal night

While astronomers suspect there are a trillion or more exoplanets in the Milky Way, we have detected only a few thousand so far. With our rudimentary methods, however, we are biased toward seeing planets that orbit close to their parent stars. This means that we are exceptionally good at finding Earth-like rocky planets close to small, red dwarf stars — like the TRAPPIST-1 system or even our nearest interstellar neighbor, Proxima b.

Planets like these are almost certainly tidally locked, which makes the question of their habitability high on the priority list.

Tidally locked planets face a lot of challenges for habitability, but it’s not impossible. This kind of planet receives a never-ending stream of light and heat on one side, with no sources of external warmth on the nightside. If the planet receives too much radiation on the dayside, the atmosphere can enter a catastrophic greenhouse feedback cycle, which would likely spell the end of any life that managed to evolve there. On the other hand, if the nightside is too cold, the atmosphere simply collapses, turning into ice that settles on the surface — which is…

Click Here to Read the Full Original Article at Space…