Astronomer Rachel Street remembers feeling frightened after a recent planning meeting for the Vera C. Rubin Observatory. The new flagship telescope, under construction in Chile, will photograph the entire sky every three nights with enough observing power to see a golf ball at the distance of the moon. Its primary project, the Legacy Survey of Space and Time, will map the galaxy, inventory objects in the solar system and explore mysterious flashes, bangs and blips throughout the universe. But the flagship telescope may never achieve its goals if the sky fills with bogus stars. New swarms of satellite constellations, such as SpaceX’s Starlink, threaten to outshine the real celestial objects that capture astronomers’ interest—and that humans have admired and pondered for all of history.

“The more meetings I attend about this, where we explain the impact it is going to have, the more I get frightened about how astronomy is going to go forward,” says Street, a scientist at Las Cumbres Observatory. As one astronomer talked about moving up observations in the telescope’s schedule, a sense of foreboding fell over her. Her colleagues were suggesting making basic observations early, before it’s too late to do them at all. “That sent a chill down my spine,” Street recalls.

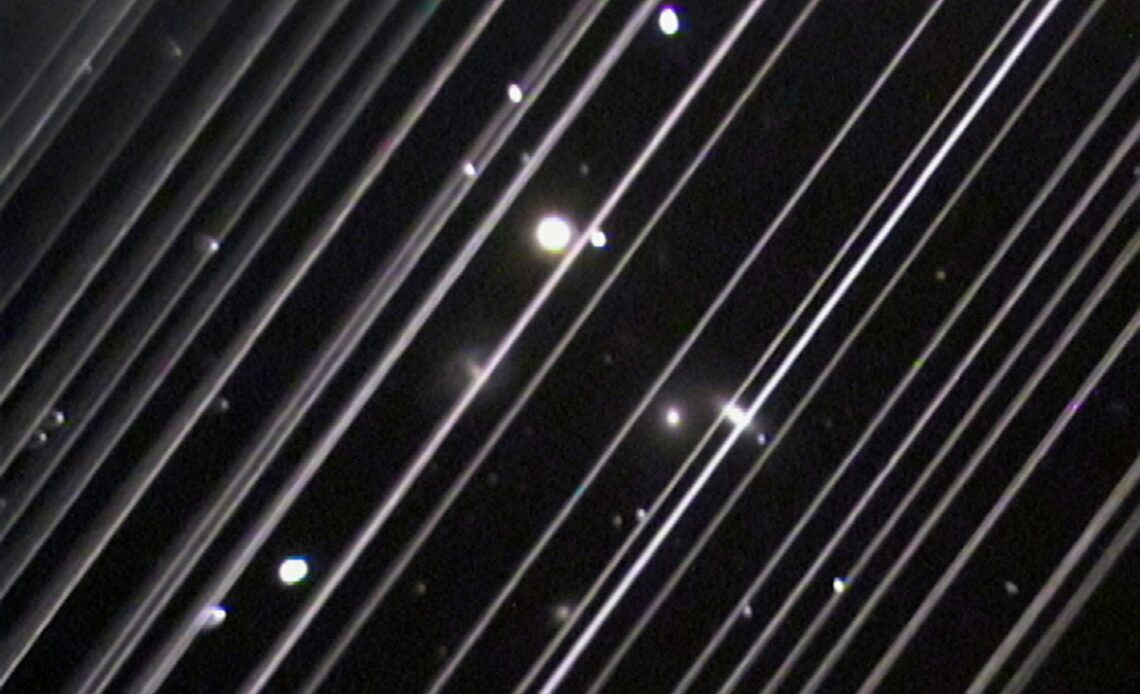

As low-Earth orbit fills with telecommunications satellite constellations, astronomers are studying how to do their jobs when many cosmic objects will be all but obscured by the satellites’ glinting solar panels and radio bleeps. Recent reports from the Rubin Observatory team and from the U.S. Government Accountability Office paint a dire picture in in which astronomy—the first science—comes under direct threat. Astronomers say that if unchecked, satellite constellations will jeopardize not just the Rubin Observatory’s future (both its overall discovery potential and its physical components), but almost any campaign to observe the universe in visible light.

“It is somewhere in the range of very bad to terrible,” depending on how many satellites launch in coming years and how bright they are, says Jonathan McDowell, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics who tracks satellites. “A few thousand satellites is a nuisance, but hundreds of thousands is an existential threat to ground-based astronomy.”

Telescope project managers are rewriting scheduling programs to avoid the new satellite swarms, but that already-impractical task will…

Click Here to Read the Full Original Article at Scientific American Content: Global…