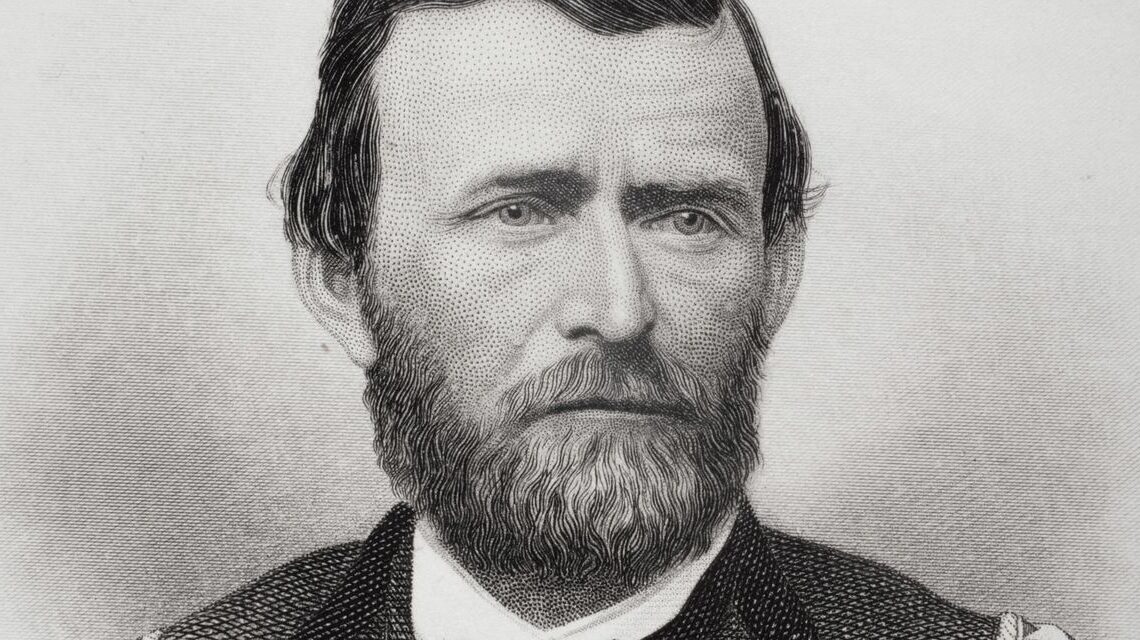

There is nothing stranger in American history than the up-and-down reputation of

Ulysses S. Grant.

Grant, who was born April 27, 1822, was the commanding general who ended the Civil War. He managed the great campaigns that captured Vicksburg and Richmond, saved Chattanooga, and compelled the surrender of

Robert E. Lee

and the main Confederate field army, and did it so well that President

Abraham Lincoln

apologized for not showing him enough confidence. Grant’s “Personal Memoirs,” published after he died in 1885, are a landmark of 19th-century American prose.

Grant may be a greater example even than Lincoln of the American rags-to-riches story. In 1861 he was working in his father’s leather-goods store in Galena, Ill. Three years later, he was general-in-chief of U.S. forces. Four years after that, he was elected president.

Still, Grant gets no respect. As a general, he was accused of alcoholism—and he was an alcoholic, by the clinical definition of the term. As a strategist, he was denounced by First Lady

Mary Todd Lincoln

as an unfeeling “butcher,” feeding the bodies of Northern soldiers into battles that simply wore away the Southern armies. As president he was derided as a tongue-tied incompetent.

Henry Adams,

the ultimate Washington insider, sneered at Grant as an upstart, “inarticulate, uncertain, distrustful of himself, still more distrustful of others, and awed by money.” Adams snarled that Grant should “have lived in a cave and worn skins.”

Certainly, Grant made his share of mistakes. He yielded to demands from his father,

Jesse Root Grant,

to ban “the Jews, as a class,” from his encampments in 1862 (an order he rescinded at Lincoln’s command and regretted as “that obnoxious order”). He…