I don’t like to talk about it. During the opioid epidemic, in order to survive, I needed high doses of these medications that were killing hundreds of thousands of people.

I have a rare disease called sarcoidosis. For 12 long years, it attacked parts of my brain, causing episodes of total blindness and vertigo so intense I would fall over when I got out of bed. Far worse was the pain it unleashed in my head.

This was pain that knifed and throbbed ― that consumed my life. Pain that would cause me to vomit repeatedly, long after my stomach was empty. Pain that left me curled in the fetal position, holding my head. Pain that kept me from sleeping for days and would not abate.

My son was a young child during the worst of these years. OxyContin pills and Fentanyl patches made it possible for me to function at all. Without these medications, there were few days I was able to leave my bed — to have a family dinner, to see my son in his kindergarten play, to sit upright and have a conversation with my husband, Jay.

I was one of the millions of Americans who needed high doses of opioids while unscrupulous pharmaceutical companies lied and encouraged doctors to over-prescribe OxyContin, while “pill mills” distributed these addictive medications far and wide, and while illegally produced Fentanyl found its way into street drugs like heroin. More than 932,000 Americans have died of opioid overdoses since 1999. This is a tragedy.

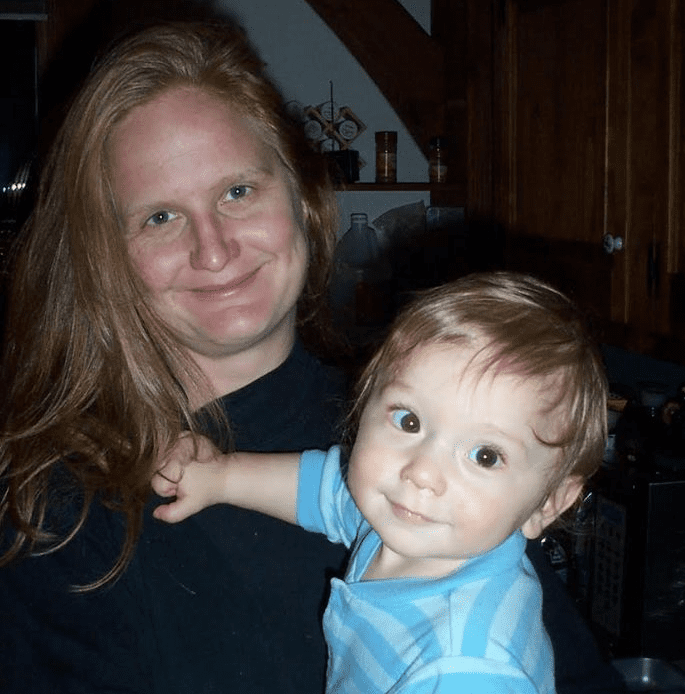

Courtesy of Rebecca Stanfel

In response, in 2016, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) issued guidelines recommending generic maximum doses for all patients, regardless of their illness or their tolerance to the medications. Recently, the CDC has walked back some of those guidelines, but the Drug Enforcement Agency continues to prosecute physicians they believe are over-prescribing narcotics. Here in Montana, several doctors lost have their jobs and/or their medical licenses for “over-prescribing” to pain patients, including those with terminal cancer.

Meanwhile, some state legislatures have set their own restrictions on opioid prescriptions. In Ohio, for instance, a doctor is allowed to prescribe only seven days of narcotic pain medicine, whether it’s for a double mastectomy or pulled wisdom teeth. All these changes have meant it’s more difficult for pain patients to find doctors willing to treat them and prescribe…

Click Here to Read the Full Original Article at Women…