On Nov. 19, the International Space Station (ISS) dodged a potentially dangerous piece of space junk left in orbit from a satellite that broke up in 2015.

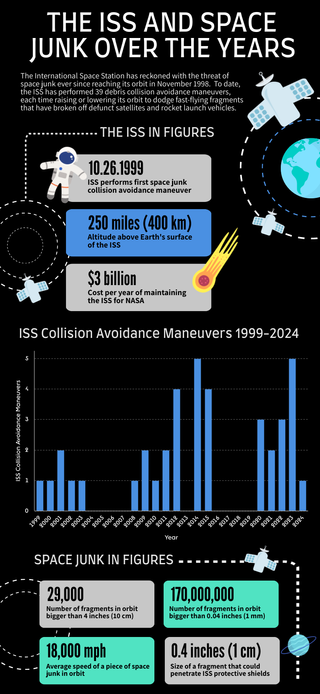

The maneuver, which involved the ISS raising its usual orbit of about 250 miles (440 kilometers) above Earth’s surface, was the first of its kind in 2024. Without it, NASA officials said the flying object could have come within a perilously close 2.5 miles (4 km) of the space station.

Space junk refers to any fragment of human-made machinery that remains in Earth’s orbit after serving its intended purpose. This year’s single dodge maneuver — technically called a Pre-determined Debris Avoidance Maneuver — marks a significant drop from the five similar maneuvers the ISS was forced to perform in 2023. It’s also fewer than those performed in 2020 through 2022, when the ISS modified its orbit at least twice per year to prevent collisions with space junk.

Astronauts aboard the ISS were lucky that so few pieces of debris came close enough to require maneuvers this year, but that probably won’t last, said Hugh Lewis, a professor of astronautics and a space junk modeling expert at the University of Southampton in the U.K. “For all we know, next week there will be three maneuvers,” Lewis told Live Science.

Related: Sci-fi-inspired tractor beams are real and could solve a major space junk problem

NASA records show the latest maneuver is the 39th time the ISS has dodged space junk since the first part of the ISS launched in November 1998, and the risk of collisions is increasing every year due to growing amounts of space junk clogging up the sky.

The ISS receives warnings, or “conjunction messages,” about incoming space junk from the U.S. Space Force, although that responsibility may soon change hands, Lewis said. A fragment is considered potentially risky if experts forecast it will enter a pizza-box-shaped area that extends 2.5 by 30 by 30 miles (4 by 50 by 50 km) around the ISS. “Anything that goes into that box, then that triggers the next phase,” Lewis said, “and they keep going through that process until they’ve identified if there is a real risk.”

The threshold to act on perceived risks is much lower for the ISS than for other spacecraft because there are humans on board, Lewis said. “They’re looking at events typically that will be higher [risk] than 1 in 10,000,” he said.

It’s raining satellites

How often…

Click Here to Read the Full Original Article at Livescience…