On York Boulevard in Los Angeles, a blurred black hole hangs on a dark wall, joined only by a pair of headphones playing looping echoes of its siblings colliding.

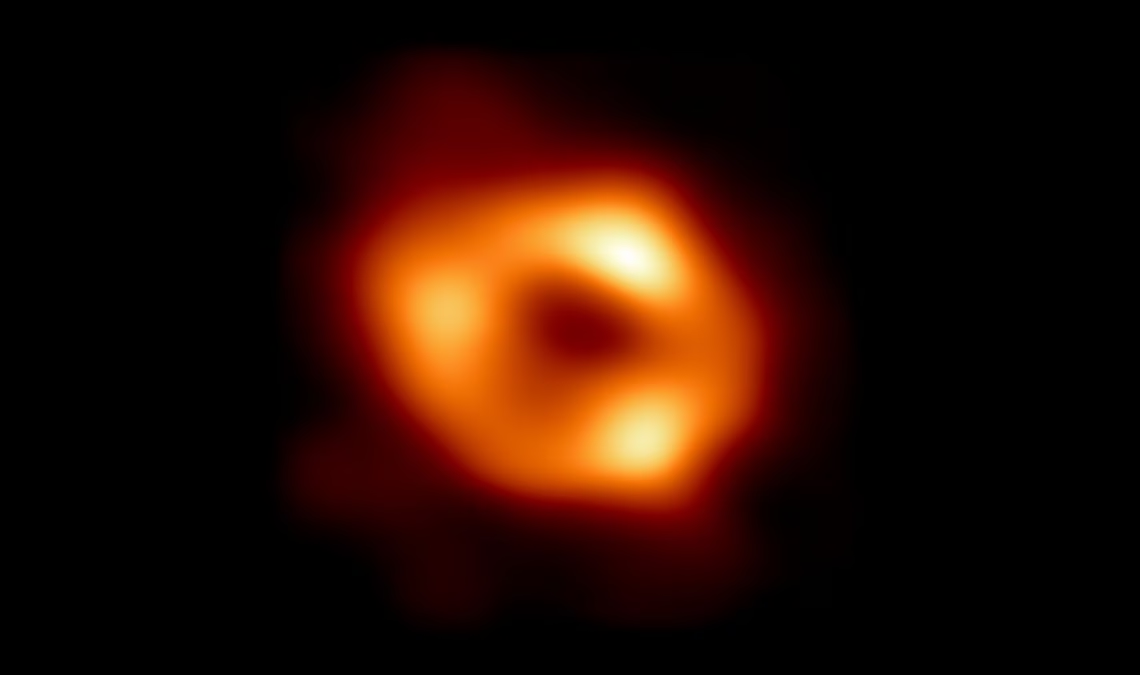

It’s a familiar scene of our galaxy’s supermassive central void, and certainly one that has flown far and wide over the years. I’d bet you’ve seen it. Journalists (including myself) have fawned over this image, affixing it to exhilarating news stories under titles like “First Image of Milky Way’s Black Hole” or “Center of Our Galaxy Revealed.” Universities have thrown it onto press releases about the Earth-spanning array of radio telescopes it owes itself to, and scientists have published it in heady studies while endearingly calling its subject just what it looks like: a fuzzy orange doughnut.

However, at the OXY ARTS gallery in Los Angeles, that abstruse portrait of Sagittarius A* looks a little different.

Isolated on its assigned wall, the 4.3-million-solar-mass black hole takes up space outside its usual astrophysical boundaries, both in the cosmos and in academia, to open itself up to artistic criticism and reflection. I have to admit, when I first saw it, my initial feeling was that it’s curious to exhibit an unedited scientific image of the cosmos in an art gallery, and especially one that artists featured across the gallery didn’t have a hand in creating. It seemed hollow, and even slightly ostentatious. But, after some time, I softened.

The intentionally empty area around Sgr A*’s frame seemed to actually punctuate its conceptual and visual weight in a way its typical online backdrop of search bars and Google Chrome tabs never has for me. The piece itself wasn’t groundbreaking in my opinion, but the choice to put it up on a gallery wall at all might have been.

This made me start to wonder whether wavelengths of art and science tend to constructively or destructively interfere with one another, or whether they are really the same to begin with. For example, something that is extremely intrinsic to art, but not to science, is the idea of individuality. A true work of art is often considered irreplicable, but an ideal scientific conclusion relies on replicability to prove itself as a universal truth.

Though, on the other hand, one of the most well-known examples of someone who sang the song of art and science is Leonardo Da Vinci, whose masterpieces are specifically built on principles of anatomy, physics and mathematics. Would it be fair to ask which of the two disciplines came first for Da…

Click Here to Read the Full Original Article at Latest from Space…